The process of decay constructs the idea only as a byproduct of the differential regurgitation of a shriveling body which is in the process of becoming less and less, without ever finding the relief of complete annihilation. This is to say […] that the troubling aspect of decay has to do more with its dynamism or gradation than with its inherently defiling nature […]. (Reza Negarestani, ‘Undercover Softness: An Introduction to the Architecture and Politics of Decay’, in Collapse VI: Geo/Philosophy, 2012.)

In the beginning there is ruin. (Jacques Derrida, Memoirs of the Blind, 1990.)

In 1946 Frank Fremont-Smith organised a set of conferences in New York that ran under the title of “Circular Causal and Feedback Mechanisms in Biological and Social Systems”. Fifteen of these events were subsequently held up until 1960, the totality of which are now remembered as the Macy Conferences on Cybernetics.1 Drawing participants from the sciences, social sciences, and humanities, the overarching thematic was to investigate and forward the operation of biological, mechanical, and social systems under the paradigm of cybernetics. Taken from the Greek κυβερνητική (kybernētikē) meaning steersman, the term itself was an attempt to emphasise systems based upon recursive feedback mechanisms of control. In biology the orientation towards such is classified as homeostasis, wherein the lifeform conditions and modifies its inbuilt parameters towards a very selective set of variables.

Mathematician and philosopher Norbert Wiener, who was one of the more famed participants at these conferences, believed that this biological metaphor could be extended, and proposed that all mechanistic and social systems could be understood through this logic — his landmark publication of Cybernetics in 1948 carried with it the subtitle: Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. As he notes: “The conditions under which life, especially healthy life, can continue in the higher animals are quite narrow”,2 and so the process of homeostatic feedback is a necessity for sustaining all complex lifeforms, and, by extension, all complex systems. Scanning the still tentatively developing realm of autonomous machines in his own day, Wiener used the thermostat as a practical example in order to demonstrate this principle of feedback: herein, the temperature of a given room is monitored and regulates itself in accordance with a pre-defined output value. The operation of this relatively simplistic device makes clear how feedback functions within a cybernetic paradigm, with these basic axiomatics parlaying into the seemingly unfathomable complexity of machine-learning algorithms powered by Artificial Neural Nets (ANN) in our own contemporary moment.3

In the direct aftermath of the Macy Conferences, ideas relating to cybernetics spiralled outwards and knotted around developments in the fields of “complex machines, […] into traffic planning, then urban and social planning, criminology and — from the early 1970s — ecology.”4 Vilém Flusser, who is mostly known in the Anglophone world for his writings on photography and the technical image, frequently integrated models from cybernetics and information theory into his sprawling theoretical agenda. His theory of the modern city draws upon these ideas and imagines it as a series of abstract relations which vary in frequency and intensity. All objects, both human and non-human alike, within the city are caught within a spatial meshwork which is populated by what he describes “as a field of flections”5. This refers to areas that exert a significant, yet invisible, type of gravitational force; like zones of intensity which function as attractors that pull in and condition a set of relations. These flections are endlessly in flux as they absorb the totality of all relational forces that become trapped within their gravitational pull. Herein, the infrastructural-complex of the city becomes reimagined as an autopoietic system — an autonomous system capable of producing and reproducing its own elements — as it ceaselessly unfolds itself in order to generate new emergent properties.

This image of a cybernetic city raises the question of who, or what, is the steersman at the helm dictating the general direction of these emergent trajectories. That is to say, what is a city for? What function does it provide? What mechanisms are in place to ensure that it codes for this function? Whom, or what, is all of this in the service of? And, what happens to the discarded elements that no longer fit the modus operandi? If we follow Flusser’s model we might very easily come to the conclusion that the most dominant flection in the modern city is that of capital. The invisible flows of the market economy are the primary legislator for modern urban planning. Funding for infrastructure is channeled into pipelines that increase capital, as everything has to ascribe to this logic of monetary investment. In accordance with the autopoietic model, individuated objects become dissolved in the overwhelming flow of processes and affects, as their function is to serve the dominant orientation of the system. Objects only become temporarily reperceptual and tangible once again if they fail or become obsolete.6 A broken door at the side of the street is more noticeable than the one located at the entrance to a building. However, in their obsolescence they provide the potential to be speculatively reimagined and reintegrated into flections in the urban field.

Such is the case with Ciara Rodger’s recent exhibition a city of beautiful nonsense, which takes its title from an early twentieth-century novel from Ernest Temple Thurston (the narrative of which is situated in both London and Venice). The pieces on display here — a series of photographs, drawings, and sculptural interventions — develop the thematic of architectural decay present in the artist’s earlier work; for instance Memories of a Nervous System (2018) and Monuments of Abandoned Futures (2019). Therein, the austere and modernist sublime of brutalist structures contour formal aesthetic investigations into runic time-capsules, with the latter’s title derived from Robert Smithson’s A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey from 1967; a speculative-travelogue which chronicled his encounters with the remnants “of an abandoned set of futures.”7 This particular vein is furthered explicitly here as a city of beautiful nonsense is framed as the result of a psychogeography undertaken by the artist in order to map the shifting diagram of the modern urban landscape. Guy Debord’s original formulation of this portmanteau emphasised geography as an objective field ruled by “precise laws” wherein the cartographic endeavour is fuelled by “emotions” and “human feelings” all in the “spirit of discovery”.8

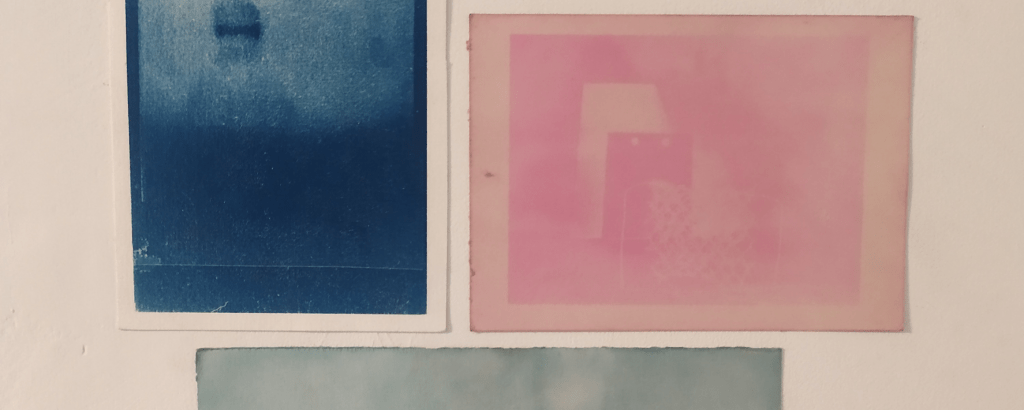

Following these cues, Rodger’s sombrely embraces an architecture of decay, with the assembled objects and images resembling the findings of an archaeological expedition that had just plumped the depths of a city in ruin. Everything feels coated in a suffocating layer of dust. The fractured content of photographs — depicting the abandoned vistas of a crumbled checkerboard floor, a disused basketball ring (the net has long since disintegrated), a busted railing, or anonymous facades — is doubled and amplified through the material form of the images themselves. Faded and fragile, in some the depicted objects recede almost entirely into the pastel chemical bloom of indigo dye or Mountbatten pink. Out of time and placed in suspended animation as their slow demise into obsolescence is momentarily halted in the static snapshot. Even when constructive forces are rendered, for instance a drawing of a building’s skeletal framework, the structures are posed in an incomplete state; on the liminal edge between actualisation and abandonment.

Ruin here can be understood as entropy. In thermodynamics this refers to the material loss of energy, with Wiener later adopting the term in order to describe the organisation of information within a system.9 Here entropy refers to the degree of disorganisation, with information (negentropy) subsequently framed as the imposition of order onto this chaos. That is to say, the ordered structure of information within a cybernetic system is negatively defined10, or, to refer back to the Jacques Derrida epigraph which introduced this text: “In the beginning there is ruin.” As such, I might propose a reenvisioning of the concept of ruin. Whilst traditionally the ruin derives its valuation from the accumulation of past histories11, the gradual decline of a monument into disrepair, it may be useful to reimagine it instead as an originary building block from which all order and meaning can emerge. The ruin herein abandons its principle symbolic tether to an eviscerated past, as it plots a course towards speculative futures.

The collapsed and decaying structures of a city of beautiful nonsense seem, to me, to evoke such a sentiment. Whilst ostensibly melancholic in nature, the clouded memory arrays which they summon appear to more forcibly anticipate the remnants of a forgotten future. Retrofuturistic in that hauntological way, this is the reinsertion of decrepit or abandoned forms back into the cybernetic logic of the modern city. The function here does not code for capital, but instead for an aesthetic experience which locates itself at an unspecified point along a future timeline. In an era where the neoliberal agenda would seek to cast a banishing spell on all forces that do not directly contribute to economic growth, it has become evermore important to maintain and record objects and events which attempt to subvert or resist the collapse of everything, and everywhere, into the quantified meter of monetary valuation. Nonsense here is not only beautiful, but also necessary.

Laurence Counihan